Romanticism had exerted a huge influence on all subsequent periods of Polish culture and on the Polish national consciousness. Romantic literature was written at a time of national bondage, which made its function very special: it was charged with upholding national identity and often replacing institutions that did not exist in the enslaved society.

Polish Romanticism also had a decisive influence on the reception of the topic of Thermopylae in modern Polish culture. Sparta in Polish culture is strongly associated with the Thermopylae motif, which symbolizes allegiance to a lost cause and has a very positive dimension in Polish Romanticism and post-Romanticism.

Here we present the motifs of Thermopylae and Sparta in three stages:

• in Juliusz Słowacki’s (1809-1849) poetry, the influence of which is exceptionally strong on the national imagination

• in Stanisław Wyspianski’s (1869-1907) dramas

• in Zbigniew Herbert’s (1924-1998) poetry, which was important to the independent intelligentsia during the communist regime.

Sparta in the “Greek” works of Juliusz Słowacki and Stanisław Wyspiański

(M. Kalinowska, Sparta w dialogach “greckich” dzieł Juliusza Słowackiego i Stanisława Wyspiańskiego (próba sformułowania pytań), in: Sparta w kulturze polskiej, vol. 1, Warszawa 2014, Wydział Artes Liberales UW, SubLupa, p. 197-218).

Sparta appears in Słowacki’s oeuvre on numerous occasions and in different ways. It appears in Agamemnon’s Tomb (1838) with its central theme of Thermopylae and the heroism of Leonidas. This poem is among the most significant works of Polish Romanticism and has had a tremendous influence upon the generations that followed. The poet travelling across Greece, visits Mycenae and Thermopylae. Mycenae makes him think about the problem of evil in history, whereas Thermopylae represents an unattainable model of heroism. The monumental figure of Leonidas personifies this heroism.

In Agamemnon’s Tomb there is an unusual fragment: “And for a long time the people cried because of such a sacrifice”, “The scented fire and broken goblet” (v. 89-90). This mysterious metaphor suggests a romantic ritual of Forefathers’ Eve (the encounter with one’s dead ancestors – the central motif of Polish Romanticism): the people who are present at the sacrifice, the people as witnesses to this Thermopylae sacrifice, and the poet who, on the battlefields, calls on the ghosts of the old Greek heroes and talks to them as though they are still alive and present for him ("[…] they must be there […] they still see", v. 75). “The Legion of the Dead Spartans" is still present at Thermopilae and it is “at the grave” that they show to the travelling poet “their bloodied chests” (v. 81). They ask the poet who came “from the sad land of the Helots” (v. 69), that is from the land of slaves, about a common or similar history: “[…] they even ask, ‘Were there many of you?’” (v. 82). This question refers to the failed Polish national uprising of 1830.

In Agamemnon’s Tomb Leonidas is presented as a naked statue, and this is a specific kind of nakedness characteristic of ancient Greek monuments. It merges the indestructible divine and the eternal with human physicality and sensuality. There is a beautiful soul in this marble statue and a struggle is being waged for it and its spiritual strength. A Poland bathed in the River Styx can become such a statue, and can regain its soul.

Juliusz Słowacki

Agamemnon’s Tomb (Grób Agamemnona)

Translated by Catherine O’Neil1

[10]

To horse!… Here, along the bed of a dry stream,

Where pink laurel blossoms flow instead of water,

As if a shining storm were chasing me,

I fly with tears and with intense, flashing eyes,

And my horse stretches his legs on the wind.

If he stumbles over a grave where knights rest – he’ll fall.[11]

At Thermopylae? – No, at Cheronea –

That is where my horse must stop.

For I am from a land where the specter of hope

Is like a dream for hearts of little faith.

For if my horse is frightened in his flight,

Then that grave is equal to – ours.[12]

A legion of dead Spartans is ready

To chase me from the grave at Thermopylae,

For I am from the sad land of Ilots,

From a land where despair does not rain down on graves,

From a land – where always after unhappy days

There always remains a sad half of the knights – half-alive.[13]

At Thermopylae I do not dare

To lead my horse through the pass;

For there must be such faces, whose gaze

Would crush the heart of every Pole for shame.

I will not stand there before the spirit of Greece -

No, I would die first rather than go there in chains.[14]

At Thermopylae – what would I say

If the knights stood up on the grave,

And, showing me their bloodied chests,

Asked me plainly: “Were there many of you?

Forget the distance of long centuries between us.”

If they asked me this – what would I say?[15]

At Thermopylae – a corpse lies still,

Without red cloak or golden sash.

It is the naked corpse of Leonidas:

There is a beautiful soul inside its marble form.

For a long time the people mourned his sacrifice,

The scented flame, and the broken goblet.[16]

O Poland! So long as your angelic soul

Is cased within a jovial skull,

So long will the executioner chop your body,

Nor will your vengeful sword cause terror,

So long will you have a hyena prowling over you

And a grave to seize you – open-eyed![17]

Cast off the last shred of those hideousrags,

That burning shirt of Deianira:

And rise, unashamed, like great statues,

Naked – washed in the mire of the Styx,

New – insolent in iron nakedness –

Not shamed by anything – immortal![18]

Let the northern nation rise from its silent grave

And frighten other people at the sight,

Of such a huge statue – made from a single stone!

And so forged that it will never shatter in thunder,

But its hands and crown will be of lightning,

And its gaze scornful of death – the blush of life.[…]

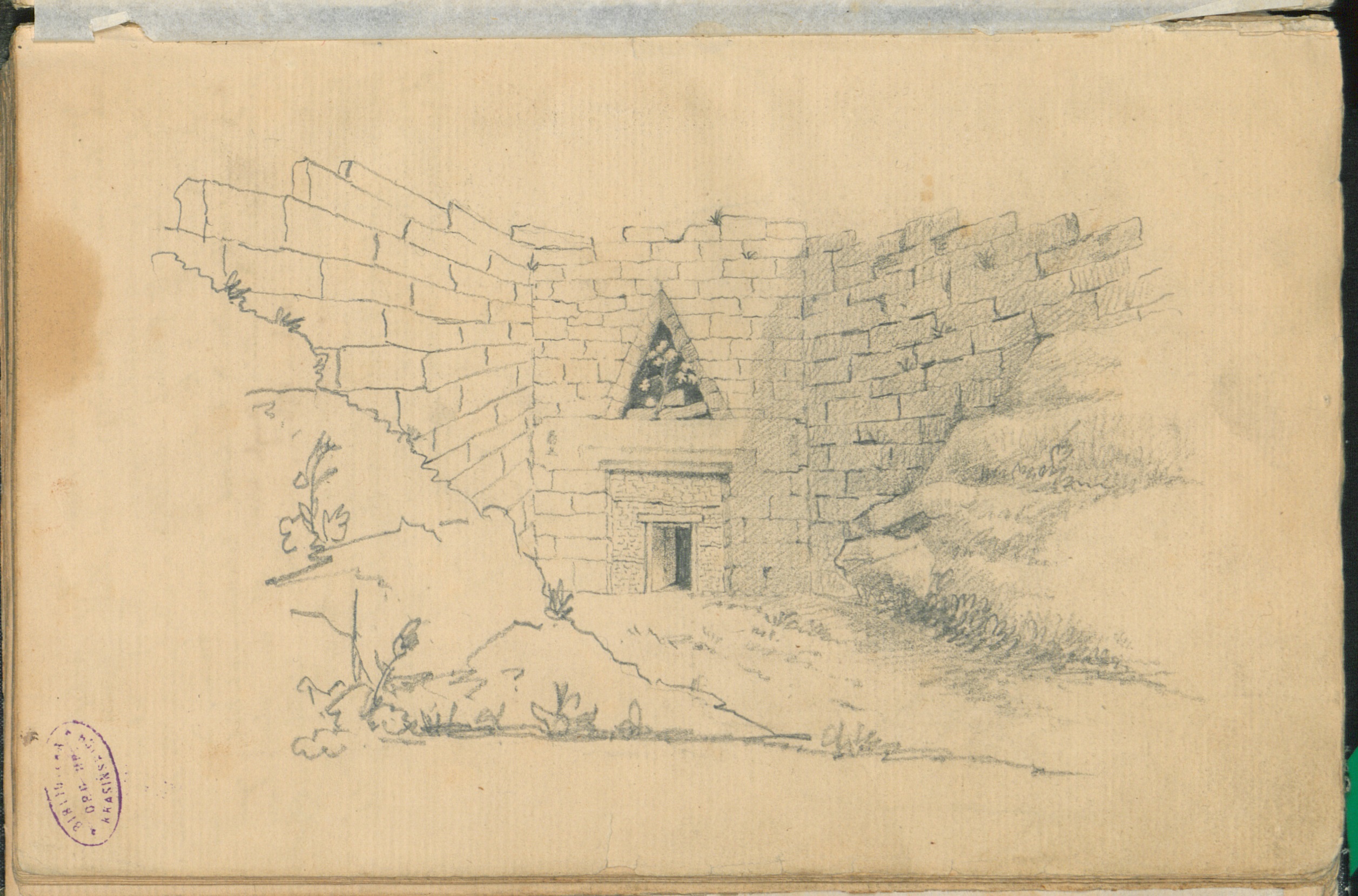

Agamemnon’s Tomb – drawing by Juliusz Słowacki, Raptularz Wschodni Juliusza Słowackiego. Edycja – studia - komentarze, vol. 1. Podobizna autografu, Warszawa, DiG 2019, p. 68.

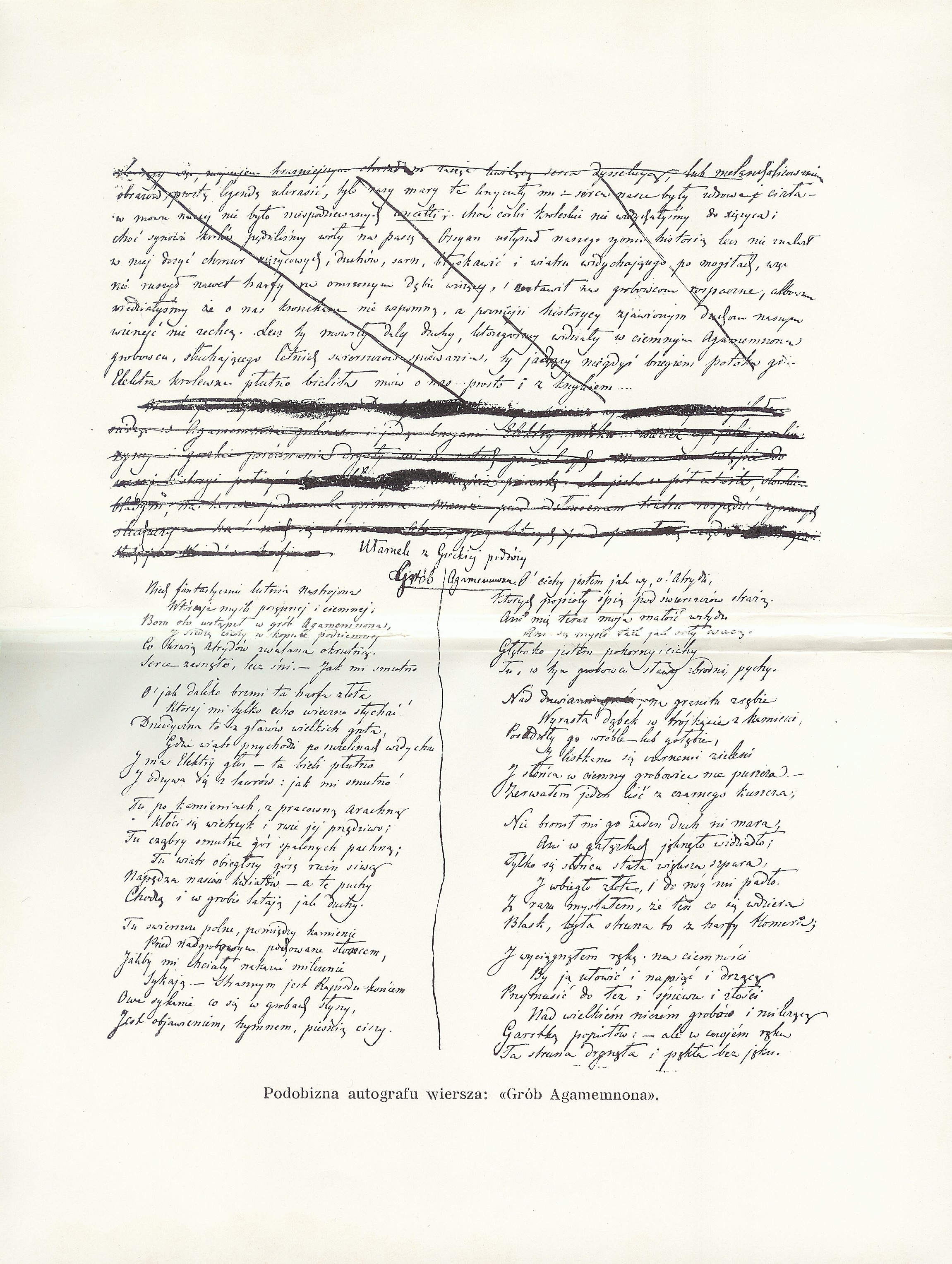

Agamemnon’s Tomb – autograph by Juliusz Słowacki, book by Bronisław Gubrynowicz, digitization by Michał Kosmulski. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In the mystical period of Słowacki’s oeuvre (after 1843), the central theme of Thermopylae and the heroism of Leonidas appears in two ways: in philosophical writings - again with the central theme of Leonidas upholding patriotism, which in Słowacki’s mystical system means a spiritual virtue indicating the way of the Spirit, and in Agezylausz [Agesilaus] – where Sparta fully becomes Poland and Agis an indomitable Christian hero. Sparta becomes Poland here but preserves its idiom… Sparta in Słowacki’s work functions as a distinct variation on the theme of battle and struggle, central for the poet’s anthropology and his vision of the world, including also for his mystical system. The cited texts clearly indicate a lasting tendency in Słowacki’s thinking and his poetry: a fascination with Sparta as a sign of a heroic anthropological model, and also the poet’s continual building of parallels between Sparta and Poland.

Wyspiański’s Greece, too, is a world of struggle, dynamics and tension, a world of activity and heroism. This dynamics – battle and struggle – brings us to think of Słowacki’s anti-idyllic and dramatic antiquity as a natural context for the “Greek” works of Wyspiański. Many features of Słowacki’s Hellenism, particularly the Polish-Greek parallel and the fascination with Homeric and Spartan Greece, inclines us to perceive Słowacki’s writing as a point of reference or even a tradition for the “ancient” works of Wyspiański as the author of Powrót Odysa [Odysseus’ Return]. We could risk the hypothesis of a kinship - though not necessarily a genetic one - between Sparta from Agezylausz and Wyspiański’s ancient Greece: this is where we find the link whereby Wyspiański inherits that ideological and artistic idea enabling him to extract from ancient Greece its raw primeval nature, created in the image of Polish, often regional or, more broadly, Slavic folk character. At the same time, however, the Spartan myth giving a privileged position to the community in a special way that shows affinity with Polish Romanticism, is not the language that could fascinate a modernist poet. In his sharp polemics with the Romantic myth of Thermopylae, Wyspiański seems to be saying that the romantic Spartan myth doesn’t have the power of salvation, it doesn’t liberate the individual from his existential tragedy or the nation from its tragic fate. It is only a tale about a beautiful and picturesque death. What in Słowacki is a sacrifice and a level of spiritual development, in Wyspiański becomes an empty gesture or – even more dangerously – an expression of a reckless rush towards death, an attraction to nothingness and empty transcendence.

Self-portrait of Stanisław Wyspiański. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Further details

(M. Kalinowska, Waning worlds and budding hopes. Anti-idyllic visions of antiquity in Polish Romanticism, in: The Missing Link: Classical Reception the “Younger” Europe, edited and with an introduction by Zara M. Torlone, Oxford, “Classical Receptions Journal” (2013) 5 (3): 320-335.)

“[…] Słowacki portrays Sparta in […] his play Agesilaus, which invokes actual historical events near the end of Sparta’s heyday and the story of the young King Agis who, wanting to restore Sparta to its previous glory, began working on reforms in 245-241 B.C. but met with opposition. In the end, the young Spartan king was cruelly murdered2. This world, not only as it existed historically but also as it is portrayed by the poet, is marked by confusion, manifold destruction, destabilization of values, which is particularly important when considering Sparta, a country that functioned in European culture as a symbol of a very specific type of culture. In Europe, a fascination with Sparta often went hand in hand with a cult for Rome and admiration for the Roman republic3. The European myth of Sparta is a myth of valour and bravery, especially military courage, the sign of an ethos not so much of individual fame but of individuals’ readiness to sacrifice themselves for their group and their country; it is also a model of upbringing connected with civic values, a soldier’s ethos, and anti-individualism. It needs adding that the models of Spartan heroism as symbolized by Leonidas and his soldiers killed at Thermopylae, intertwined with the ideals of chivalry - so greatly important for the Polish gentry, had appeared in earlier works by Słowacki as unattainable models of patriotic behaviour. The more expressive this myth, the stronger the impact of its destruction…”

“Słowacki in Agesilaus portrays a Dionysian, dark Sparta: this is an anti-idyllic Greece where a lack of harmony, uncontrolled violence and madness are part of existence and its heroic struggle with the extreme situations of individual and collective being4. At the same time, though, the Spartan ideal - though transformed - becomes the foundation of Christian heroism . In the pre-mystical period of Słowacki’s output - up to the early 1840s - the poet referred to Spartan ideals to build a model of heroism devoid of transcendental, religious hope. After the mystical transformation that he experienced in the early 1840s, this became a model of the heroism - open to the demands of the Spirit - of an eternal transformation leading to God, a mystical heroism with a metaphysical aspect. This is the road travelled by Słowacki’s imaginings or dreams about the Spartan-Pole: from the pre-mystical Agamemnon’s Tomb (1838), inspired by his visit to Mycenae and Thermopylae, part of the travel poem Journey to the Holy Land from Naples, to Agesilaus, a very unusual and unfinished mystic play, written feverishly and in haste, inspired, with a sense of mission to pass on the revealed truth about the world of the Spirit5.

The protagonist of this work, Agis, is a man of gentleness and calm spirit on the one hand, and thus can be called an evangelical character, but at the same time there is a violent side to his behaviour, contradicting the earlier image. He wants to restore Sparta to its former glory, to its true greatness, the Lycurgean Spartan character, seeing it precisely in valour, honesty, dedicated service to the state and the community, forgetting about oneself. Agis has the qualities of Christ. Slowly, as the dramatic events unfold, his fate is more and more like the story of Christ. We can also say that this play has a very special construction related to Słowacki’s mystic worldview. It is such a structure of dramatic time in which the king of Sparta repeats (!) the fate of Christ: yes, repeats, and not just anticipates it.

Sparta in this work is seen from the perspective of the poet’s mystical system - the “genesian” system: Słowacki appraises it in terms of arrested development. In his “genesian” output the poet subordinates humans to the ruthless laws of the “Eternal Revolutionary Spirit” always demanding sacrifice and changing the fossilized forms of the world. Agis, one of the characters from this period of Słowacki’s work, appears in history in order to move frozen Sparta, halted in its development, to give it a new quality and new character, revive it, push forward its development and its necessary transformation of forms, lend it a new, Slavic (!) tone.

In Agesilaus we observe as if in statu nascendi the tragedy changing into a mystery play, the mystery of Christ’s Passion. The protagonist, King Agis, sacrifices himself and this is a Spartan sacrifice - for the nation, but also a Christ-like sacrifice with a Christ-like and evangelical dimension. In the special poetic world of Agesilaus, the two sacrifices and the two heroisms are equated. And, it is very important for Słowacki’s mystical ideas that King Agis sacrificing himself is marked by Slavism. This is how Słowacki combines the Slavic idea with the Spartan world, gentry Poland with Spartanism (which is perceptible in the way the space of the play is created: in its artistic logic, Spartan reality is intertwined with the reality of historical gentry Poland).

Sparta in Słowacki’s play is an anti-idyllic and anti-Apollonian world: people’s states and emotions, interpersonal relations, the rules and regulations of community life - all this paints an image of a dark, troubling world, Dionysian in its own way, lacking harmony, equilibrium, certainty. It is fear, uncertainty, unspecified danger, cruelty, that determine this vision of a waning world. Constantly appearing images of dark marble, temple ruins washed in cold moonlight, are accompanied by chaos and the unpredictability of human feelings and violent emotions. Here, the human world is extreme in every aspect: in cruelty, in sacrifice, while the spirit - the most important element of Słowacki’s mystic system, who decides about the heroes’ fate, is just as cruel, this is “a spirit without mercy”, drawing the persons of the drama into its timeless order of a world of eternal sacrifice and dedication. If to these qualities we add melancholy and sadness which permeate all the elements of the drama, the result is an almost complete image of the tone in which Słowacki’s anti-idyllic Greece manifests itself.

Together with the creation of disturbing images with hard-to-interpret semantics, the play features the theme of the song of the ancient chorus, continued by the Romantic poet as he resurrects the genuine, living, though almost forgotten singing of the chorus in Greek tragedies. This is the song of the chorus drawn from the earliest archetypal areas, continuing wherever the boundary becomes blurred between ritual and theatre, individual and group, myth and poetry. It is the Romantic poet’s song that “re-sounds” the ancient and constantly renewed choral song. At the same time, this is song created as an echo repeating “the tone of distant crying and singing”. It is the song of old myths and profound experiences and passions allowing people to unite with the romantically understood cosmos. It is song as a link between the two cultures. However, the great rhythm of the living world-cosmos in Agesilaus defines a transformation of the world and humankind, accomplished not in Athens but in fact in Sparta, where “man’s primeval force / Shone as a white statue”6. Thus, in Agesilaus the chorus is a sign of the world’s moving, the stimulation and renewal of its higher meanings, and especially a new “hearing” of the meanings of ancient culture embodied in the Romantic poet’s revival of the song. In Słowacki’s tragedy that “choral music” beats out “life’s great rhythm”7, from the spirit of the song tragedy is born… The Romantic poet revives the long forgotten and long unheard voice of the ancient chorus, its song understood in a very Romantic way…[…]”

Transl. Joanna Dutkiewicz

A Portrait of Juliusz Słowacki by James Hopwood. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Grażyna Halkiewicz-Sojak, Zbigniew Herbert’s Sparta

(G. Halkiewicz-Sojak, Sparta Zbigniewa Herberta, in: Sparta w kulturze polskiej, vol. 1, p. 345-356) Summary

“Zbigniew Herbert toured Sparta during his first Greek journey in September 1964. He didn’t return to the region during subsequent Greek travels. This traveller-poet’s perception of Sparta can be reconstructed from an excerpt in the essay “Attempt at a Description of the Greek Landscape” and Herbert’s correspondence with Magdalena and Zbigniew Czajkowski. For Herbert, this was not a space that inspired the artistic imagination, but the Spartan political system and its apologetic and critical interpretations present in the tradition of European thinking did encourage him to offer some reflections. His thoughts polemicize with the praise of Lacedaemonian culture initiated by Plato and Xenophon, which is the effect of the poet’s mistrust of abstract ideas and holistic systems and is part of the oppositions that Herbert found important: abstract versus concrete and idea versus life. The poet rejected utopias – actually, revolutionary utopias more often than retrospective ones (the latter including utopian thinking related to the Lycurgus tradition). He was a critic of Spartan education and its reduction of individual qualities and emotions (cf. the essay “Cleomedes”).

Next to this critical aspect, however, we can also find references in Herbert’s work to the heroic image of the Greek polis, to the tradition of Leonidas and the defence of Thermopylae. In “Prologue”, “Photograph” and “Report from the Besieged City” we find allusions to the Spartan tradition as laying a foundation for heroism and sanctioning such values as honour, patriotism, keeping one’s word. These accents return particularly in those works in which Herbert invokes the theme of a lost city: Lvov and, in a different aspect, Warsaw”.

Grażyna Halkiewicz-Sojak wrote that Spartan motifs and allusions in Herbert’s oeuvres reveal an axiological duality”. After Halkiewicz-Sojak had completed this paper, the Zbigniew Herbert archive became available and it is now possible to find extensive notes for a publication that Herbert had planned on Thermopylae; these notes confirm the duality noted in Halkiewicz-Sojak’s paper. Herbert was very sceptical about an anti-individualist Sparta, though he valued Thermopylae and what it represented very highly.

Further details: see M. Kalinowska, Sparta w niepublikowanych rękopisach Zbigniewa Herberta. Rekonesans, „Sztuka Edycji”, 2017: 1, p.45-54.

Conclusions

Setting aside these tensions which show the multidimensionality of the theme of Sparta in various areas of Polish culture, what generalisations can be drawn reconciling the different points of view? The fact is that Sparta functions in Polish culture – and this is probably the most important common denominator of our studies – as a positive model of individual, self-sacrificing dedication to one’s country, and to a worthy although often lost cause. In this sense, Sparta in Polish culture is a model of valour and Thermopylaean sacrifice, even if this model is represented not only by Leonidas but also by King Agis. As such, it is a personal, individual model, chosen intentionally, and available to everyone… This positive model does not include the blind military force that destroys individuals, nor is it interested only in a strong state’s corporality, violence and capacity for expansion. Norwid pointed to the dangers of such a non-Thermopylaean, non-self-sacrificing, non-Greek Sparta (i.e. incompatible with the Romantic ideal of freedom). It is a paradox that, after the experiences of totalitarianism and the fascist fascination with the Spartans, the 20th century did not demolish that “Thermopylaean” ideal of Sparta. Miłosz or Herbert, who – like Norwid – were sceptical about Sparta with its destruction of the individual and its synonymity with violence, essentially did not destroy the “Thermopylaean” model, so deeply ingrained in Polish culture, as a model of valour and self-sacrifice, a voluntarily chosen proof of fidelity to a lost but priceless cause.

Collaboration: Kohn Kearns, Ludmiła Janion, Anna Hućko, Joanna Dutkiewicz.

Juliusz Słowacki, Agamemnon’s Tomb (Grób Agamemnona), transl. Catherine O’Neil, in: Poland/s Angry Romantic: Two Poems and a Play by Juliusz Slowacki, ed. P. Cochran, B. Johnston, M. Modrzewska and C. O’Neil, Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2009, p, 160–163. ↩︎

M. Brożek, Agis i Kleomenes [commentary], in: Plutarch z Cheronei, Żywoty sławnych mężów, transl. and ed. M. Brożek, Wrocław, Ossolineum, 1976, p. 305-306. Plutarch’s text was Słowacki’s inspiration. ↩︎

E. Rawson, The Spartan Tradition in European Thought, Oxford, Clarendon P., 1991. See also: G. Highet, The Classical Tradition. Greek and Roman Influences on Western Literature, Oxford: University Press, 1967, p. 394 and subsequent pages). ↩︎

I wrote more extensively about the play in the paper: The Myth of Sparta in Juliusz Słowacki and Cyprian Norwid’s Dramas. Romantic Reinterpretation of Greek Heritage – the Polish Variant, in a collective work being prepared for publication at the Collegium Budapest (project “Multiple Antiquities and Multiple Modernities in Nineteenth-Century Europe”, 2005) (M. Kalinowska, The Myth of Sparta in Juliusz Słowacki and Cyprian Norwid’s Dramas. Romantic Reinterpretation of Greek Heritage – the Polish Variant, in: G. Klaniczay, M. Werner, O. Gecser (eds.), Multiple Antiquities – Multiple Modernities. Ancient Histories in Nineteenth Century European Cultures, Frankfurt/New York, Campus Verlag, 2011, pp. 547-561). ↩︎

For more about Słowacki’s Agezylausz, and especially the Greece-Poland motif, the role of the chorus, and the “mystery aspect” of the play, see J. Skuczyński, Odmiany form dramatycznych w okresie romantyzmu. Słowacki – Mickiewicz – Krasiński, Toruń: Wydawnictwo UMK, 1993, p. 152 and subsequent pages. ↩︎

This is the metaphor used by the chorus in Agezylausz, speaking of Sparta’s importance for the history of humankind. See J. Słowacki, Agezylausz, [in:] idem, Dzieła wszystkie, ed. J. Kleiner, vol. 12, part 2, Wrocław, Ossolineum, 1961, p. 93. In the original: w Sparcie, gdzie “pierwsza człowieka siła / Posągiem białym świeciła”. ↩︎

Cf. ibidem, p. 96. ↩︎